PIRATE

RADIOS : THE STORM IS ABOUT TO BREAK

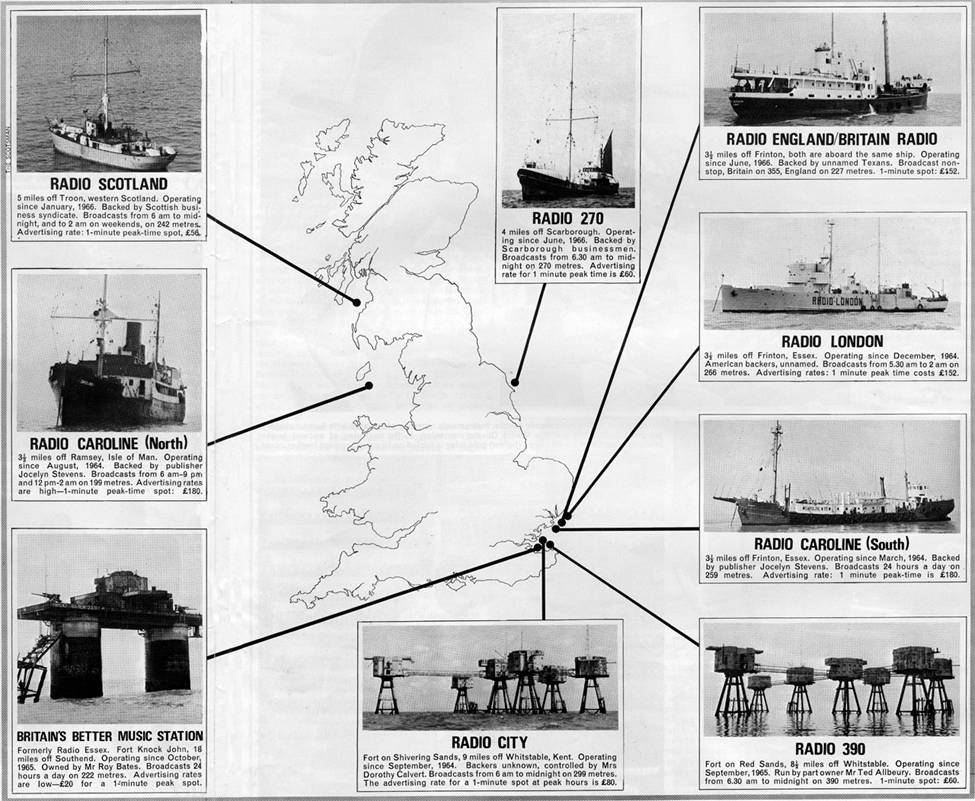

The opening shot in the Government's campaign

to silence the pirate radio stations is a summons against Radio 390 answerable

on November 24; and a new anti-pirate Bill is likely to become law by March.

ADAM LYNFORD

reports

Sir Alan

Herbert, as chairman of the British Copyright Council, has described the pirate

radio stations as " a scandal at Britain's own front door. Every liner

passes close to them: the stranger can almost hear the lawless laughing at the

Crown." Ever since March 29, 1964, when the first of the pirates-Radio

Carolinetook to the air, they have been the targets of such criticism, although

they have also attracted a great number of impassioned defenders.

The

Government has been slow to act; it was only in September that the first

summons for illegal broadcasting was issued against one of the ten pirate

stations. Radio 390 must appear at Canterbury magistrates sessions on November

24. The charge is being brought under the Wireless Telegraphy Act of 1949,

which prohibits public broadcasting without a licence from the Post Office to

do so. The only holder in Britain of such a licence is the BBC.

The crux of

the case is also the Government's reason for the long delay in issuing such a

summons: the question of the tourt's jurisdictioli over Radio 390, housed in a

disused anti-aircraft tower on Red Sands, eight-and-a-half miles offshore in

the Thames Estuary. The difficulty lies in the definition of territoria)

waters. In 1878 the limit was laid down as being three miles, but in the last

two years Orders in Council and amendments to the Continental Shelf Act have

been introduced to cope with the requirements of drilling in the North Sea.

These Orders and amendments in some cases altered the definition of the "

base line "for the limits, from the previously fixed position of the low

water mark on British shores.

The Post

Office emphasises that this " is no test case." A second summons

against another pirate aboard a fortBritain's Better Music Station, on the old

Fort Knock John, 18 miles from Southend-wil) be heard by Rochford magistrates

court on November 30. Radio City, the third fort-based station -on Shivering

Sands, nine miles off Whitstable, Kent-can possibly expect to be the next

recipient of a summons. The maximum penalty under the Act is a £100 fine and/or

three months' imprisonment, together with the confiscation of equipment.

These court

actions are just a whiff of grapeshot from the authorities; the 1949 Act is

apparently effective only against the stations based on forts. The really big

guns will be wheeled out in March 1967 when the Marine Etc Broadcasting

(Offences) Bill is expected to become law. This Bill's provisions will enable

the authorities to fight not only the forts but also tbc seven ship-borne

pirates, a thing the Government apparently cannot do under the 1949 Act.

Mr Ted

Allbeury, managing director of Radio 390, is confident that the summons to

appear at Canterbury will do him no damage-" otherwise we wouldn't have

bothered fighting it." But when the Marine Bill becomes law, he believes,

" We'll all have to pack up and go home. Like all spiteful legislation,

it's really very good."

The Marine

Bill was published in the Commons last July and is expected to be taken through

both Houses by next February, then to come into operation a month later. Its

provisions take the form of a tourniquet around the pirates' lifeline: all

these who serve or supply them would commit an offence; it will be unlawful to

provide a ship or radio equipment for use in pirate broadcasts, to install or

repair the equipment, to supply or carry any goods to the stations, or to carry

anyone to or from the stations; any person who supplies records, tapes or other

recorded material for pirate programmes will be legally answerable. Similarly,

it will be an offence to advertise on the pirate stations, either direct or

through an advertising agent, and to publish details of the broadcasting

programmes. Proceedings under the Bill may be taken in any part of Britain and

its provisions may be extended to the Isle of Man or the Channel Islands.

Pirates

will not be able to seek refuge from these laws by advertising foreign products

or by obtaining supplies or advertising material from the Continent, because

the Bill has been given extra backbone by an agreement made between Britain and

six other European nations in January 1965. The signatories to the

agreement-Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Luxemburg, and Sweden -have enacted

similar preventive measures to those of the Marine Bill against their own

citizens supplying goods, equipment, or advertising to the pirate stations.

Holland toe has taken the same measures against pirates.

A Post

Office spokesman stresses that the Bill does not provide for use of force:

There will be no need to resort to boarding parties. On indictment, the maximum

penalties are two years' imprisonment, or a fine, or both.

The pirates

talk bravely of fighting these new measures. A Radio Caroline spokesman said:

" Of course, the Bill will have some effect on our operations; certain

changes and alternative arrangements will have to be made-but there is no

intention of our going off the air." This viewpoint is a general consensus

of the pirate stations' views. These mysterieus "new arrangements " and

hints of help from " other quarters " seem sufficient to keep them

afloat-they firmly believe and hope.

An even

greater pall of secrecy cloaks the finances of the stations. Information is

refused on the grounds that they are entitled to withhold it because they are

not public companies. The more prosperous, larger stations such as Caroline,

London, and 390 admit that they are making " reasonable profits."

Radio Caroline has paid off its initial investment (an undisclosed amount);

Radio 390 expects to pay off its investment by

March of next year; and Radio London does make a profit, although there are no

facts available about its initial investment. Britain's Better Music Station

also makes money, but running a station, they all agree, does not mean "

having a licence to print money."

Radio 390 expects to pay off its investment by

March of next year; and Radio London does make a profit, although there are no

facts available about its initial investment. Britain's Better Music Station

also makes money, but running a station, they all agree, does not mean "

having a licence to print money."

Advertising

rates on the stations vary enormously; stations often allow discounts, trimming

their charge to snit the pocket of their client. Rates also vary according to

whether it is for a customer in their own area or a national product; whether

the " spot " is prerecorded or spoken by the resident disc jockey. A

minute at peak hours-generally from 9 am-2.3o pm-may cost anywhere from £56 on

Radio Scotland to £180 on Radio Caroline. Advertising is generally limited to a

maximum of six minutes in an hour.

One of the

chief charges against the pirates is that they infringe the law of copyright by

playing records without permission from the British Copyright Council. In fact,

four stations-Radio Caroline North and South, Radio London, and Radio 390-do

pay the Performing Rights Society. The payment is based on a scale rising to 31

per cent of their advertising revenue. No figures of the actual amount are

forthcoming either from the pirates or from the Society. A Society spokesman

explains that they never reveal figures of this kind, as they are, in this case

too, " a matter for private negotiation and agreement."

The Society

is in the vanguard of bodies opposing the pirates, and a spokesman complained

of the " delicate " situation they are in of accepting money from the

pirates: " We have been put into this situation by the pirates. If we were

to refuse the money, the pirates would publicise the fact and we would look

really silly."

Curiously,

the BBC's objections contain no mention of the competition for listeners; the

official view is only: " The pirates are illegal. They pay no regard to

international agreements on the allocation of wavelengths, and cause severe

interference with foreign stations." But it was the trend set by the

pirate stations that influenced the BBC to introduce " late " (after

12 pm) recorded music shows. They chose as one of their disc jockeys for this

purpose Simon Dee, who announced the very first programme on Radio Caroline,

the dean of all the pirate radio announcers. On hiring Mr Dee, the BBC

declared: " His experience will be very useful." (Radio Caroline's

transmitters, incidentally, were set up by experienced ex-BBC engineers.)

The future

for the pirates is overcast by the cloud of the Marine Offences Bill. But it

may have a silver lining in a Cabinet White Paper on broadcasting, now drawn up

for publication. It is thought to contain proposals for setting up a hundred or

more local commercial radio stations throughout the country.

Several

very respectable companies have staked claims, but possibilities for further

investment still remainand a shortage of personnel experienced in running radio

stations will soon develop. There is a strong possibility that pirate backers

and staff will plug these gaps. A government invitation for them to do so would

be a brilliant exercise in redeployment, and would save the expense and effort

required to enforce the provisions of the new Bill.

Bron : The Illustrated London News, 19 November

1966